Chasing Clout: How Com Networks Turn Violence into Social Currency

Todays post examines the demographics, types of harm, and underlying motivations driving the 764 network and similar groups, where violent extremism intersects with child exploitation and nihilistic ideologies. This week the goal is to shine light on the make up of the network and the reason why minors are targeting other minors, or carrying out offline acts of violent extremism. This analysis will detail the age, gender, and social dynamics of individuals within these networks. It will further unpack the spectrum of harm—from psychological abuse to criminal activity—that perpetrators inflict for social currency. By understanding why these threat actors engage in escalating transgressions, this post aims to shed light on the mechanisms fueling one of the most disturbing trends in digital extremism.

Demographics

Size of Network

764 does not exist in a vacuum; rather, it is part of a wider network known as Com. That network can be broken down into three key pillars: Extortion Com (where 764 is located), Cyber Com, and Offline Com (where accelerationist networks like Maniacs Murder Cult or No Lives Matter are found). Com, as a loose network of hybridized threats, is a complex phenomenon to visualize, so let me use an example a colleague of mine at the Eradicate Hate Global Summit gave during our panel on 764: Com is like a cafeteria in a high school or middle school; each group or community in Com is a table in that cafeteria, and 764 is one of those tables.

Com and the 764 network have been growing, particularly over the past two years. Currently, there are approximately 12,000 unique accounts across 78 Extortion Com Telegram groups. Beyond these, there are 303 additional groups in the wider Com network. This is, in reality, an underestimation of the size of membership and groups in the network. To give a sense of scale, during our session at the Eradicate Hate Global Summit panel, the speaker from NCMEC (National Center for Missing and Exploited Children) showed some alarming statistics about the reports they have received linked to 764: in 2023, there were 260 tips sent to NCMEC; so far in 2024, there have been 1,100 tips sent in, which is a 423% increase. Of further concern, whereas the majority of tips NCMEC receives come from platforms and law enforcement, more than 50% of the tips linked to 764 have been reported by victims, family members, and friends. This discrepancy is another alarming trend.

Age

What is important to note is that Com is about minors harming and targeting other minors. Perpetrators are on average 11-17, with some in their early 20s (there have been a few cases of older offenders aged 40+). The victims, on the other hand, are aged 8 to 17. Both perpetrators and victims are getting younger. The age dynamic is what stands out: traditionally, child sexual exploitation and abuse (CSEA) is a crime carried out by adults on minors; however, this is not the case in this network—it is minors psychologically and physically abusing other minors.

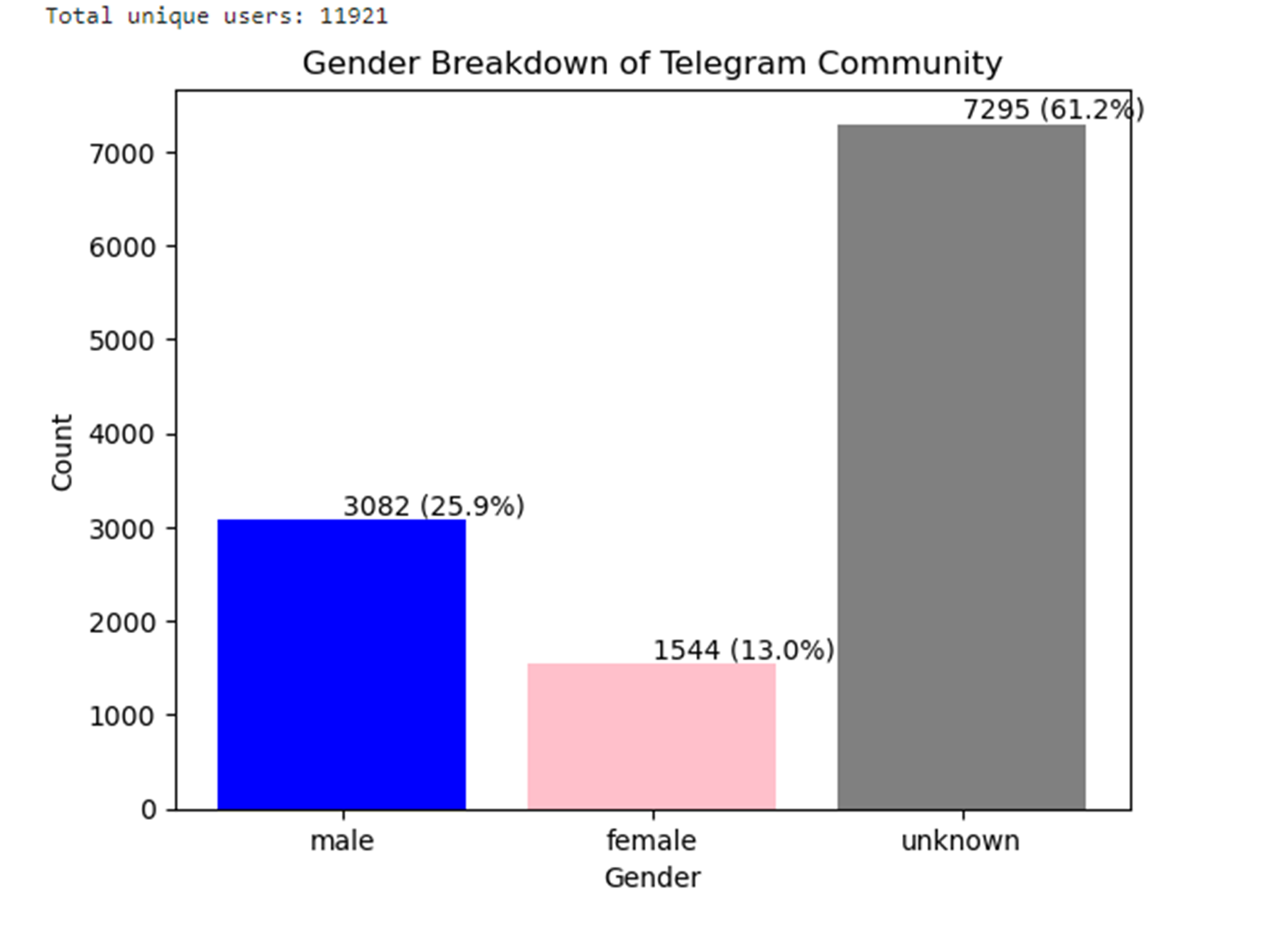

Gender

I have been experimenting with ways to better understand the demographics of the Com network, which is mostly anonymous/pseudo-anonymous. In my current experiment, I used the BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) large language model to identify gender linguistic markers linked to the unique IDs of users in the network to attribute them a gender score. I analyzed 2.3 million posts from 11,921 unique users. Out of this, 7,295 users (62%) could not be linked to linguistic gender markers. This gave me a sample of 4,626 users to whom we can attribute a gender score. Out of this sample, 66% are identified as male and 34% as female. Now, this is an experimental sample of the gender demographics, but it gives us an idea of the network dynamics. Of note, minor males and minor females can both be victims and perpetrators; further, if you are queer, trans, or a "femboy," your intersectional identities make you a more attractive target for victimization.

Clout

Sextortion Com, Cyber Com, and Offline Com are all focused on clout chasing (being popular within their community) and documenting one's criminal successes by publishing videos and images of one's acts. There are a few exceptions I want to highlight that are not only about clout chasing but also hold militant accelerationist ideation and objectives: Maniacs Murder Cult, No Lives Matter, Cult Brotherhood of Blood, Cult of White Misanthrope, Mord Waffen, and their successors. These groups also focus on offline criminal and violent extremist activities. Nonetheless, like wider Com networks, they push for the documentation and dissemination of their own violent acts, aiming to inspire and mobilize a new generation of extremists while terrorizing the general public.

If the acts target a specific individual, the information is released in a “LoreBook.” These threat actors have entire archives dedicated to the acts they have carried out, convinced others to do in their names, or those who worship them have offered as a token of their dedication to them. These types of actions and multimedia serve as a form of cultural currency within these ecosystems. The influence and popularity of individuals rely heavily on the quality of one's "content," the regular creation and generation of this content, and the extreme nature of the content (the more extreme it is, the more popularity points you get).

So, what is the value of a victim's safety and well-being? What do the victimizers get that is so valuable to them that they are willing to commit some of the most atrocious acts? The heinous and traumatic acts victims are subjected to are done simply for the "lolz," for administrative privileges in a chat or server, for a special title or tag next to their username, to be put on a roster from one of the Com groups, or for access and entry into the most private and closed networks of these communities. They commit these criminal acts for internet popularity, for likes, for popularity votes in a Telegram poll.

These "rewards" sought by these minors are ephemeral, as titles can be removed or lost by an admin who thinks their content is lacking, or if they become a victim or get "cucked." There is a rapid reversal of power and popularity dynamics, yet nevertheless, the minor predators in this network are continuously chasing the next boost to their clout and popularity. Ninety-nine percent of these minors commit these acts with no ideological or political goal in mind—they do not wish to change society or take down a political entity. These acts by minors against other minors have no value or goal to these individuals; they are purely nihilistic, misanthropic, and seek to sow chaos for the sake of chaos.

Action = membership, content = access: to gain access to the "premium" servers and chats, an individual needs to create content (which means committing a crime). By creating content and sharing it, an individual can also be added to the "roster" of a specific group (think of this as finally being invited to the "cool kids" lunch table). Notably, members of Com are more criminally active and more willing to carry out acts of criminality and violence than those in traditional violent extremist spaces, where individuals are often content being ideologues and keyboard warriors.

Victims, survivors, and predators in these spaces have stated that the more harmful and heinous you are, the more status you will ultimately have. For the predators in the network, if you could get a girl or boy who was ungroomed and then groom them for the first time, that gave you status. If the victim was good-looking, that would give you more points. If they had an eating disorder, you got them to self-harm—the skinnier the victim was and the deeper they cut, the more status you got as your content was "better." Again, content is the currency of the landscape.

In-Group Out-Group Dynamics

Traditionally, as Della Porta has explained extremist communities are structured by strong in-group and out-group dynamics, where solidarity within the in-group fosters hostility toward an identifiable out-group. This dynamic is evident across many ideological groups, from nationalist militias to religious extremists, where a shared identity and defined external "enemy" reinforce group cohesion and collective goals. However, in networks like Com, particularly Sextortion Com, these social dynamics are inverted. In-group affiliation offers no protection from victimization; instead, harm is inflicted indiscriminately across members as well as external targets, driven by a nihilistic drive for status and "good content."

Within Com, the absence of a defined out-group creates an environment where violence and degradation are the primary social currencies. Members target anyone within reach—including other members—in a cycle of "clout-chasing" that views harm as entertainment and social capital. This internal targeting contrasts with the usual mechanisms of in-group loyalty and protection observed in extremist movements, making Com a uniquely self-destructive network. The Ouroboros metaphor—a snake consuming its own tail—aptly describes this dynamic, where the network sustains itself by continuously recycling harm among its members.

This breakdown of traditional group boundaries aligns with the emerging research on nihilistic extremism and "inverted" extremist subcultures, where acts of transgressive violence are no longer tied to ideological or political aims but are performed for personal gratification, social status, or purely nihilistic motives. The Com network’s misanthropic and self-destructive nature resembles what criminologists term “deviant subcultures,” where rules are inverted, and destructive behavior is normalized to achieve social validation within the group. This is especially relevant as "status" within the Com network is defined by the capacity to shock, harm, or "entertain" through increasingly extreme actions.

This lack of in-group protection and the constant internal threat of victimization present unique challenges for intervention. Unlike traditional extremist groups, where deradicalization efforts might appeal to ideological shifts or address the protective aspects of group loyalty, approaches targeting Com and similar networks must grapple with their intrinsic lack of ideological coherence and self-harming culture. The fluidity of targeting in Com, paired with its nihilistic motivations, complicates rehabilitation efforts, as many members remain trapped by fear of social ostracization or by trauma cycles that bind them to the group.

Ultimately, the Com network reflects a disturbing shift in online extremist spaces, where harm becomes both a means and an end. The violence within the group sustains its social fabric, and the lack of ideological grounding or external enemies points to a deeper cultural trend within digital extremism—one that prioritizes chaos, degradation, and clout over conventional extremist goals. This shift underscores the need for tailored approaches that address the unique social and psychological factors driving participation in these misanthropic, self-consuming networks.

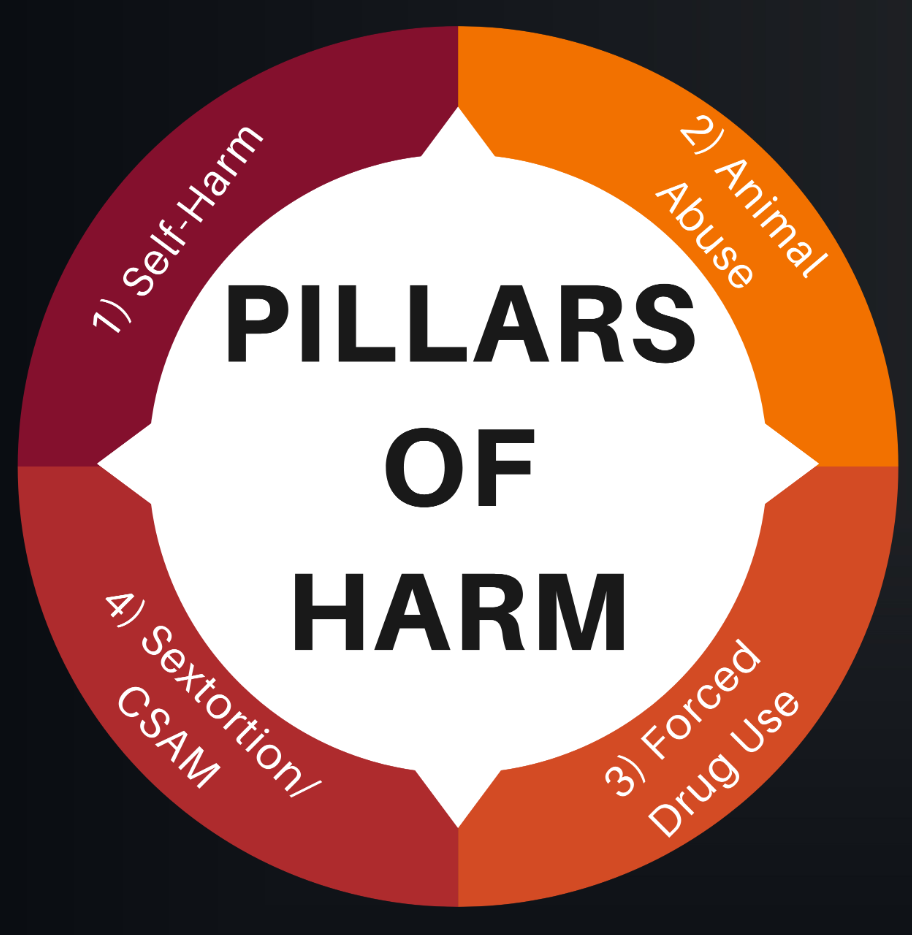

The harm caused by these networks doesn't end with psychological abuse or clout-chasing. It's also reflected in the different types of self-injurious and criminal behavior perpetuated in these spaces. Below, I've broken down some of the specific categories of harm taking place within Extortion Com, Cyber Com, and Offline Com.

Harm Types

1) Self-Injurious Behavior

Self-injurious behavior is a significant and distressing part of these networks. Self-harm, including cutting, is prevalent among members, especially minors. In these spaces, self-harm is often used as a form of currency or proof of loyalty, with participants sharing photos or videos of their injuries to gain clout or acceptance within the group. This behavior is normalized and even celebrated, which can make individuals feel pressured to harm themselves further to fit in or maintain their status. Eating disorders are also heavily encouraged and exploited within these groups. Victims, who are often vulnerable and seeking validation, are pressured into extreme weight loss, with members demanding evidence of their starvation or other unhealthy behaviors. This cycle reinforces a dangerous dynamic where young people compete to demonstrate how far they are willing to go, pushing their bodies to the limit. Discussions around suicide and substance abuse are also alarmingly common. In some cases, predators within the network actively encourage others to engage in suicidal behavior or substance use, recording these acts to generate content that will increase their status within the group. These networks prey on the insecurities of young individuals, exploiting their mental health struggles for entertainment and clout.

2) Animal Abuse

Animal abuse is another shocking aspect of these networks, used both as a demonstration of loyalty and as a means to initiate new members. The acts of abuse are extreme and involve deliberate cruelty, including animal crushing, burning, stabbing, drowning, and even bestiality. These acts serve as a brutal form of initiation, where members prove their commitment to the group by participating in or documenting these heinous activities. Animal abuse in these settings is not just about harming animals—it is about displaying a willingness to engage in extreme violence without remorse. This willingness to harm vulnerable beings is seen as a marker of strength and dedication to the network. The content generated through these acts is then circulated within the community, further solidifying the abuser's status and demonstrating their loyalty to the group. This kind of behavior desensitizes members to violence and normalizes cruelty, creating an environment where escalating levels of harm are required to maintain one's position.

3) Extortion and Sextortion

Extortion and sextortion are the principle activities in these networks and represent one of the most insidious forms of control. Doxxing, or the practice of exposing someone's private information, is commonly used to intimidate or manipulate victims. Once a victim's personal information is exposed, they become vulnerable to threats and coercion, which are often used to force them into complying with the network's demands. Minors are especially at risk, as they are pressured into performing sexual acts, which are then recorded and used as leverage for further exploitation. This cycle of sextortion is often used to generate content that members can share to gain influence within the group. The victims, who are usually other minors, are manipulated into a position where they feel powerless, unable to seek help due to fear of exposure or retaliation. The content generated through these coercive practices becomes a form of currency, allowing perpetrators to gain clout and recognition within the community. This dynamic not only victimizes individuals repeatedly but also perpetuates a culture of fear and control. The victims are vulnerable individuals who are often actively self-harming. Victims tend to be more loyal to their abusers/offenders than they are willing to go to law enforcement, friends, family, or clinical help.

4) CSEA

Child Sexual Exploitation Abuse (CSEA) and exploitation are at the core of the harm perpetuated by these networks. Victims, often very young minors, are coerced into sharing intimate images or videos. These materials are then circulated within the group as tokens of status, with members gaining recognition based on their ability to produce or distribute such content. The sharing of CSEA is not limited to a small subset of individuals but is instead a widespread practice that is used to maintain power dynamics within the network. The victims are often manipulated through a combination of threats, coercion, and psychological manipulation, making them feel as though they have no choice but to comply. The distribution of CSEA within these networks is treated as a means of gaining influence, with the most shocking or graphic content being the most highly valued. This practice not only causes immense harm to the victims but also reinforces the toxic culture of exploitation and abuse that defines these spaces.

5) Criminality / Violent Extremism / Murder

Members are often involved in acts of violence such as stabbing, tire slashing, and arson. These acts are carried out not for ideological reasons but as a means of gaining clout and recognition within the group. The more extreme or dangerous the action, the more respect it commands among peers. Swatting, which involves making false emergency calls to provoke an armed police response, is another tactic used by these groups to intimidate or retaliate against individuals. This practice puts innocent lives at risk and is seen as a way to demonstrate power and influence. While some members may have extremist beliefs, the majority of these actions are not ideologically driven. Instead, they are performed to gain status within the group, with individuals willing to escalate their behavior to increasingly dangerous levels to achieve recognition. The criminal acts committed by these networks are a reflection of the broader culture of nihilism and misanthropy that pervades these spaces, where harm is inflicted purely for the sake of gaining temporary influence.

In the End

These behaviors represent a deliberate escalation of harm and chaos, where clout serves as the primary motivator: the higher the risk or the more shocking the act, the more status and respect it commands within the network. The convergence of child exploitation and violent extremism within networks like 764 reveals a grim evolution in digital-age threat landscapes, where nihilism and social validation drive escalating harm. Trauma plays a significant role in sustaining these communities, binding individuals to the group out of fear of losing social bonds or facing the reality of their actions. This trauma cycle often transforms victims into abusers or recruiters, replicating the harm done to them by preying on others. These dynamics create considerable obstacles to intervention, as individuals frequently hesitate to seek help due to shame and the illegality of their acts. This analysis underscores the urgent need for nuanced approaches to countering these groups and protecting vulnerable populations. As these networks evolve, understanding their complex motivations and dynamics is critical to disrupting their influence, mitigating their reach, and better informing prevention and victim support efforts.