Extremism Unmasked

My latest analysis for the Global Network on Extremism and Technology

Original Post can be found on GNET

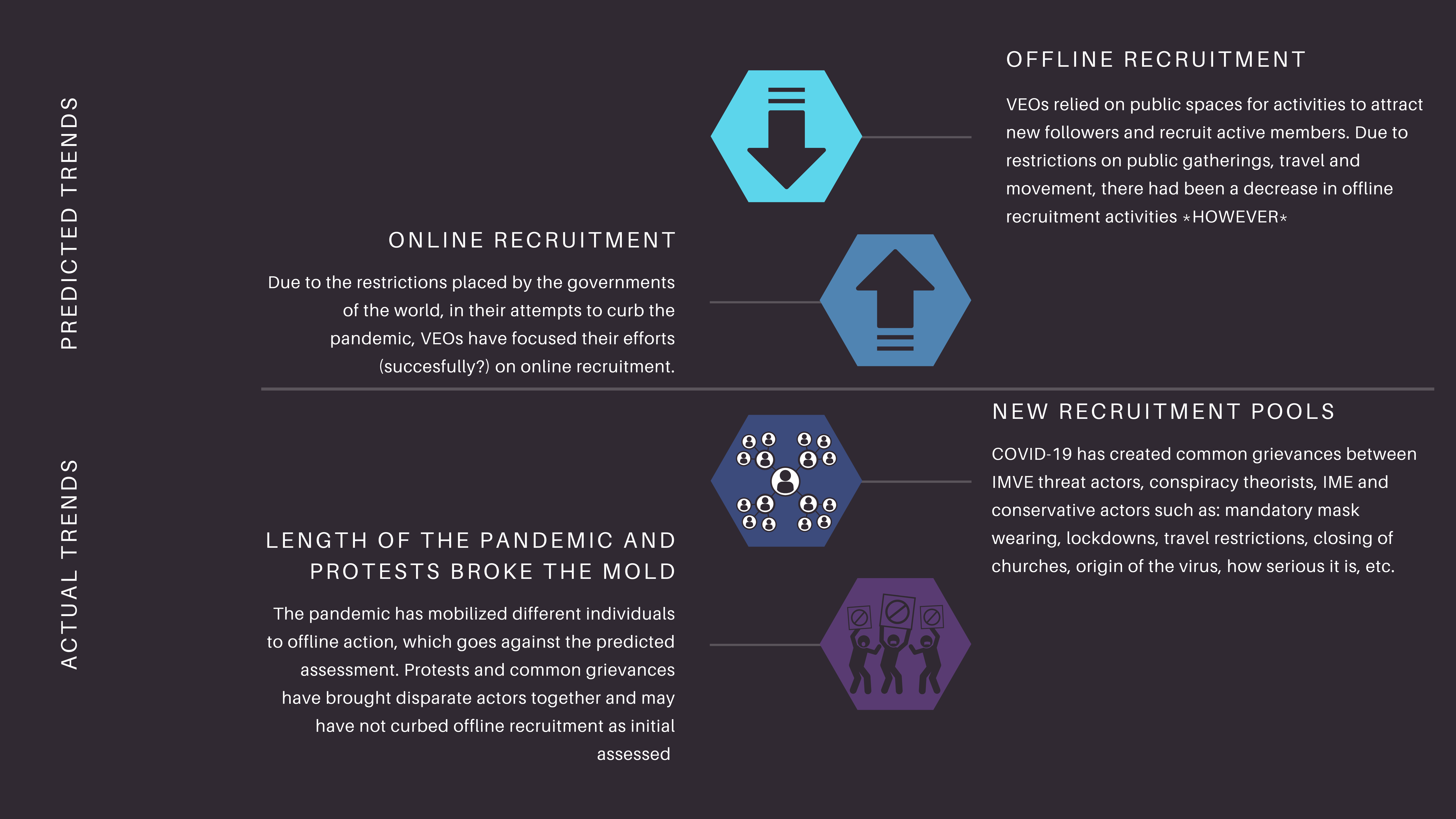

Early analysis in 2020 raised two points, the COVID-19 health restrictions would likely have an impact on offline recruitment from violent extremist organisations (VEOs), while simultaneously boosting their efforts at recruiting online. It is difficult to answer if online recruitment was successful, and I have yet to uncover any convincing findings about this as we cannot talk about recruitment in the traditional sense.

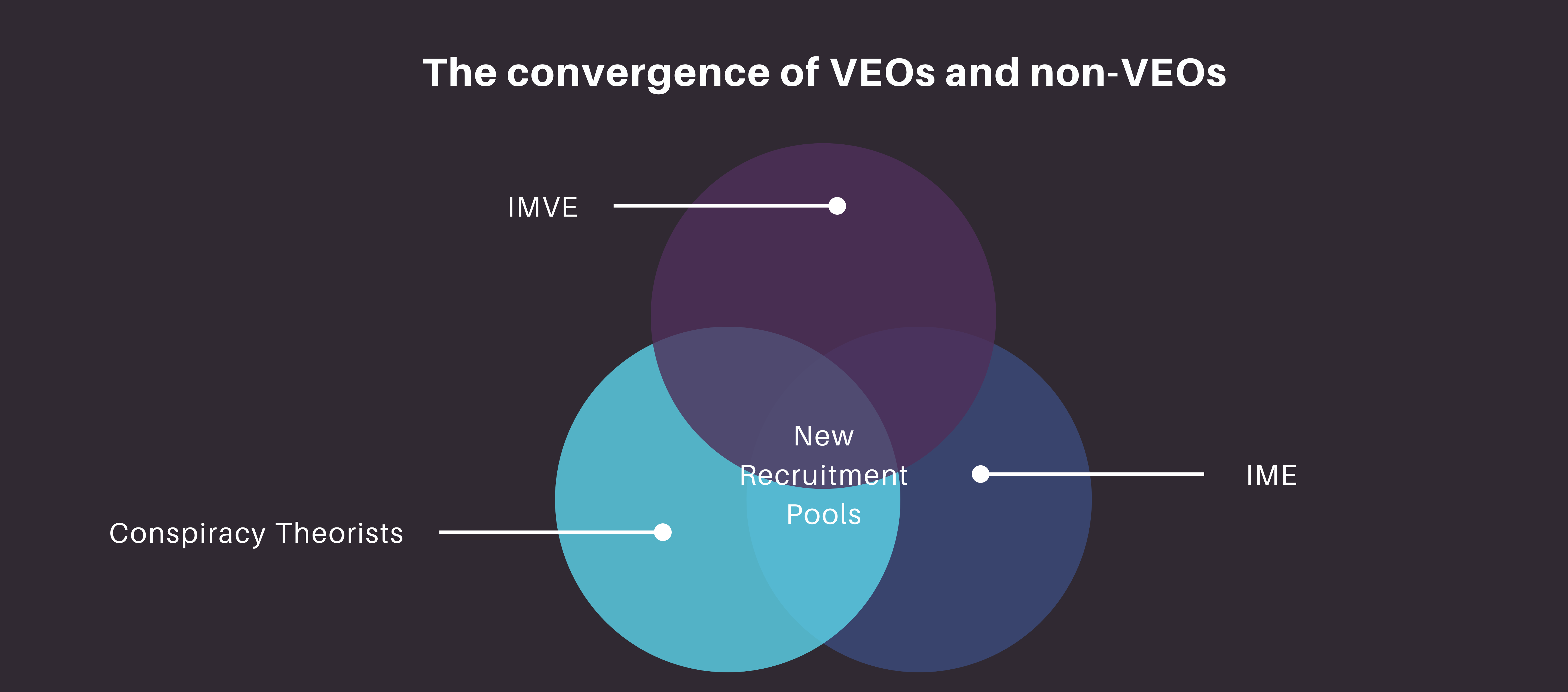

When we talk about recruitment, there is a difference between a VEOs doing outreach, grooming and vetting vs. individuals globally affected by the same crisis, sharing similar grievances finding themselves in similar ecosystems and forming online networks/offline movements. What some research has highlighted is there has been continued recruitment during the pandemic. My research has shown that new recruitment pools, where non-VEOs and VEOs/ideologically motivated violent extremist (IMVE) actors have merged, have also formed. Pastel QAnon is an example of this phenomena.

QAnon has been able to adapt themselves to the pandemic, by absorbing narratives and beliefs from Sovereign Citizen ideologies, III%, militias, boogaloo, etc. as these spaces have networked with each other in a symbiotic process of radicalisation. This symbiotic relationship went both ways, as in turn these various VEOs, adapted and absorbed some of the COVID-19 conspiracies promoted by QAnon and others in these ecosystems. In some instances the relationship was not symbiotic, rather some accelerationists leveraged these networks, as well as, leveraged COVID-19 and political instability to advance their neo-fascist traditionalist views and mobilise some VEOs to violence.

This should not be surprising in some ways, though COVID-19 as a crisis was able to bring the best out of many people, the same crisis was also able to bring out the worst in others. COVID-19 health restrictions were seen as evidence of a deep state (or big government) conspiracy encroaching on individual freedoms, capitalising on chaos, panic and fear to push conspiracies into the mainstream. Whilst such narratives placed blame on different actors and incited varying levels of violence, many share a common anti-government conspiratorial framework. These cognitive and psychological phenomena are on display as various COVID-19 related grievances bring people together.

The nascent phenomena (yes, a year is a short period of time even in a rapidly changing space) of violent extremists, extremist and conspiracy theorists coming together in the numbers we have seen is a novel phenomena especially with the amount of cross-pollination that is observed. VEOs have been maliciously using social media to create and amplify disinformation on a large-scale, by taking advantage of vulnerabilities in our social media ecosystem and by manipulating people through conspiracy theories. The pandemic has acerbated existing flaws in our societies, in our democratic institutions, and on social media platforms bringing them all to a head at once. The lack of preparedness, and the inability of key societal sectors to take these vulnerabilities seriously have led to half measures or over reactions, which have made the situation worse in the short term. Long term impacts are yet to be known, as we are still living through this period. What is clear now is that actors and organisations that did not engage with each other are now sharing grievances and ecosystems, which is of concern.

This has been augmented by large deplatforming events since the start of the pandemic, but none was more important than the January 2021 deplatforming of extremists and MAGA actors. In the wake of the mass deplatforming of extremist actors and those involved in the 6 January insurrection, alt-tech platforms and secure messaging apps received an influx of new users.

These events will impact the evolution of VEOs with regards to radicalisation and mobilisation of IMVE actors. First, this presents multiple challenges as some of these platforms do not have the capacity to appropriately respond to the threat due to a small or non-existent trust and safety team. In other cases, these platforms do not care and will not cooperate with outside actors. Secondly, the multiplicity of platforms now being used presents potential radicalisation pipelines, many of which are novel in the counterterrorism (CT) space. Therefore, existing toolkits and threat assessments were not built upon the current paradigm shift that occurred in extremist digital ecosystems. Third, alt-tech spaces haven’t seen numbers of users as we’ve seen since February 2021, and we have yet to even feel the repercussions of this event. Taking telegram as an example, Islamic State or Terrorgram never had channels with tens of thousands of users, let alone hundreds of thousands. The networking of extremist actors with threat actors is of concern, as their symbiotic relationship grows. Not only are “Twitter and Parler” refugees now adopting violent extremist ideologies and narratives, but threat actors are adopting conspiracies they mocked in the past.

Therefore, I would like to highlight 4 objectives of VEOs/IMVE threat actors:

- Undermine: The COVID-19 health measures have played an important role on VEOs who perceived these measures from federal, state/provincial, and local levels as impositions on their freedoms. These necessary and urgent actions played into the existing narratives of many of these VEOs who promoted anti-establishment and anti-government narratives, have taken every opportunity to protest, challenge and attack the “system”.

- Reinforce: VEOs have used the pandemic and its societal impact to reinforce their narratives, resonance has been particularly strong with homesteaders, militias, preppers, accelerationists, as well as amorphous movements that fall outside the VEOs box such as QAnon. Some either perceive the pandemic as fake and a way for governments to seize power over citizens, or the “mismanagement” of the crisis by governments.

- Recruit: The pandemic has created several factors that have led to an increase in potential recruitment pools: the economic impact of the pandemic, the perceived government overreach, social isolation, social and political uncertainty. Moonshot CVE discovered significant increases in searches for far-right extremist content in both Canada and the United States following implementation of lockdowns. Some have not been recruited by VEOs, but have been radicalised into extremist movements like QAnon, anti-lockdown, anti-mask, etc.

- Inspire: COVID-19 has led to a fair amount of action from VEOs or IMVE actors, whether it was the Boogaloo Bois, Michigan Wolverines, III%, QAnon, Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, etc., to individual actors not affiliated to an organisation. Actions have ranged from derailing a train, to burning down cell towers, targeting vaccine clinics, attacking government buildings, targeting politicians, attacking protesters, attacking law enforcement, etc.

Therefore, when the influx of those who were deplatformed, and who are also frustrated after more than a year of government restrictions, established VEOs with narratives about government overreach and how to deal with them are attractive options in some instances. This is especially true for those who perceive those electoral systems have failed them, law enforcement has failed them, the health system has failed them, and their information war has failed. At this point extremist solutions are more attractive. This disenfranchisement and the impact of the pandemic has led to an increase in potential recruitment pools: the economic impact of the pandemic, the perceived government overreach, social isolation, social and political uncertainty.

Ultimately the pandemic has played an important role in the IMVE and CT space. This is not surprising. However, simply because we appear to be at the tail end of this pandemic, it does not mean the issue will disappear. Those who have been radicalised have a trained behaviour and an emotional need to be filled and they will seek to do so somewhere else. Deplatforming may be a sexy solution that gives the appearance of success, but it is a double-edged sword. Not deplatforming would have had its own consequences, but now we need to accept that this will not solve the issue. Platforms and decision makers love to push for deplatforming because it gives the appearance that they are doing something to deal with an issue. However, these are short-sighted decisions. Deplatforming alone without comprehensive approaches that would take societal reconstructions and changing the way that we deal with the factors that lead to radicalisation is a poor option. The deplatforming band aid is great because you want to pass the public opinion test, but it deals with actors without attacking the core causes or those who fall outside ‘groups’ and sweeps the issue under the rug.

We need to deal with the factors that lead to an individual’s radicalisation, which are simply not a list of things at times; up until then, there is nothing that is going to be done that will eliminate the issue. We can see what happened with 6 January- the massive amount of deplatforming has led to potentially a few hundred thousand new users going to Telegram alone. These are individual accounts that have been engaging with not only QAnon content but more extremist content. Yes, they’re not on Facebook and Twitter and maybe having less of an impact on the everyday discussion; however, the fact that they’re in these more radical spaces means that they will become in some cases more dangerous threat actors than they would have been. Platforms and governments need to ask themselves how beneficial it is to remove a group of shit posters on Twitter and Facebook, knowing the alt-tech spaces they will end up in are inhabited by violent extremist. Will deplatforming lead to more radicalisation to violence? We don’t have enough data to answer that at the moment, but it is something that needs to be considered. Especially as platforms will have a caretaker role, not only from a content management perspective but also from a user threat reduction perspective.