Tempora Mutantur: 2022 a Year in Review

The trends I have observed from ideologically motivated violent extremist milieus and actors in 2022

As the year 2022 draws to a close, it's important to reflect on the significant trends and events related to ideologically motivated violent extremism (IMVE) and terrorism that have occurred over the past 12 months. While threats to national security are always a concern, and some factors remain a constant, there have been shifts in how the threat is perceived and how it has manifested in recent years. This year end review will highlight some of the larger and emerging trends I have found in my own analysis of violent extremism and terrorism in 2022 and that will continue to be of interest in 2023.

Global Trends

There are two global trends that are important to highlight from the start when talking about 2022 trends. We came into this year with a decrease in terrorist attacks that were attributed to a group, where out of the 5,226 terrorist attacks recorded in 2021 only 52% were attributed to a group. (IEP, 2022) Furthermore, politically motivated terrorism overtook religiously motivated terrorism in 2021, with religiously motivated terrorism declining by 82% in 2021. (IEP, 2022) In the last five years, there have been five times more politically motivated terrorist attacks than religiously motivated attacks. (IEP, 2022). In the West, the number of attacks has fallen substantially over the last three years, in 2021 there were 59 attacks (a decrease of 68%) and 10 deaths (a decrease of 70%) that were recorded in 2021. (IEP, 2022) From the perspective of terrorist attacks, what we are seeing and will continue to see, especially in the West is that the threat landscape is increasingly shifting towards actors that are not motivated by religious ideologies and that these threat actors are less likely to be part of a group.

From the Depths is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Top 10 Trends I Have Observed

These larger trends trickle down to the threat actors and ecosystems I focus on as part of my research on IMVE, which is defined as:

Proponents of ideologically motivated violent extremism (IMVE) are driven by a range of influences rather than a singular belief system. IMVE radicalization is more often caused by a combination of ideas and grievances resulting in a personalized worldview that is inspired by a variety of sources. IMVE includes gender-driven, xenophobic, anti-authority, and other grievance-driven violence.

I want to highlight that these trends are biased and grounded in my own personal observations over the past year and my own research interests, but supplemented with reporting from other sources.

1) Moving Beyond the Organization

The first is how the landscape continues to shift towards post-organizational violent extremism and terrorism (POVET), “that is to say violent extremist and terrorism where the influence or direction of activity by particular groups or organisations is ambiguous or loose.” (Davey, et al., 2021) What I have continued to observe in 2022 is that organizational structure is becoming less important in the context of domestic violent extremism as a convergence of ideological affinities becomes more potent than the hierarchical terrorist organizational structures of the past in instigating and motivating violence. When "groups" do appear they are often relatively short-lived, with new ones springing up drawing inspiration from similar core texts and ideologies. There is also a dimension of aesthetics and branding where everyone and their uncle is launching a new Waffen XYZ, or Division EFG. This post-organizational phenomenon is not new. In the 1980s, Louis Beam published his tract “leaderless resistance” and put it online in 1992. Recent high-profile violent extremist terrorist attacks and foiled plots in Canada, the United States, Slovakia, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and Sweden (to name a few) have shed light on self-radicalizing, logistically autonomous individuals who have little or no relationship with proscribed terrorist groups or organizations with a top-down structure, but are instead linked to loose transnational extremist networks that primarily operate online. For IMVE organizational structure is becoming less important because ideological affinities have a greater ability than previous hierarchical organizational systems to incite and inspire violence.

This trend is also echoed by several governments, in example the UK Intelligence and Security Committee annual report, released December 2022, which states that:

In terms of drivers, it is clear that the online space is key. Historically, a journey into ERWT entailed real-world contact with organised groups and individuals in-person: the internet has removed these barriers. Self-Initiated Terrorists are now radicalised, and can radicalise others, online from the seclusion of their bedrooms. Online content such as videos of terrorist attacks, manifestos, propaganda and ideological literature can all be found on a variety of platforms and at different levels of encryption – progressing from mainstream social media sites through to fringe networking sites, gaming sites, dedicated extremist websites and Secure Messaging Applications. Potential recruits can be channelled into ‘echo chambers’ isolated from opposing viewpoints – although not everyone will be guided through the system by a recruiter. Some find their own way through to the more extreme material.

This is also echoed by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation in their own annual report which highlights their main concern are from attacks carried out by single individuals:

Both religiously and ideologically motivated violent extremist groups have produced sophisticated online propaganda which calls on lone actors to engage in violence, and provides technical advice to do so . And our greatest concern continues to be the threat of a terrorist attack undertaken by a single individual or a small group— irrespective of their specific ideology. Such attacks are difficult to detect and can occur with little to no warning.

Similarly, in an October 2022 strategic intelligence assessment, the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Bureau of Investigation highlighted:

Domestic violent extremist lone offenders acting independently and without direction from specific groups are the primary actors in lethal domestic terrorism incidents. The FBI and DHS assessed lone offenders and small groups of individuals would continue to be the primary actor in these attacks and would continue to pose significant mitigation challenges due to their capacity for independent radicalization and mobilization and preference for easily accessible weapons. The FBI and DHS assessed multiple factors, including perceptions of – or responses to – political and social conditions and law enforcement and government overreach, would also almost certainly continue to contribute to domestic violent extremist radicalization, target selection, and mobilization.

Both Canada, via the CSIS Annual Public Report, and the EU, via the European Union Terrorism Situation and Trend Report, also highlight that lone actors remain the primary perpetrators of terrorist and violent extremist attacks in Europe and Canada. Though groups still matter and play a role in assessing the threat posed by violent extremism and terrorism, the landscape is moving more and more towards a post-organizational reality, which will have important impacts on how violent extremism is researched and analyzed.

2) The Ecology of Ideologically Motivated Violent Extremists

The contemporary IMVE landscape is not a unified entity, but a collection of disparate and conflicting projects. Some grasp the most powerful offices in the world, others fester on online platforms, others organize street demonstrations, and some carry out mass murders. IMVE actors are not linked to a specific platform either but represent a fractured and fractious landscape of different social networks, messaging apps, video streaming platforms, and image boards. There is a self-sufficient propaganda feedback loop that is cross platform. Which is why, based on my analysis of the past year, I have found that ecosystems and the networks that comprise them play a critical role in radicalizing and inspiring people to commit acts of violence. These networks and ecosystems are made up of a variety of contradictory and ad hoc undertakings rather than being ideologically cohesive.

The New Zealand government found in their annual report that “Increasingly we have seen crossovers and combinations of different ideologies, with comingling of political, identity, faith, and single issue agendas, sometimes combined with or exacerbated by trending topical issues and conspiracy theories.” This echoes findings from the Canada, American, British, Australian governments and the EU. Alex Newhouse in his 2021 analysis of neo-fascist accelerationist networks is a good example of how the threat landscape has been changing and will continue to do so into 2023.

3) Case Study of the Post Organizational Reality and Ecology of Violence

The Christchurch attack continues to have an impact, three years later, on IMVE successful and failed plots over the past 18 months. The Buffalo supermarket and the Bratislava LBGTQ+ bar attacks, as well as failed plots in Italy and Sweden continue to highlight the impact of the Christchurch attacker on IMVE ecosystems and attackers.

In our analysis of the Buffalo attack, we found that each of these attacks, and dozens of smaller instances of violence and attempted violence, followed a “cultural script.” In each instance, this crop of extreme-right terrorists who claimed inspiration from the Christchurch attack have sought to exceed its death toll, incite further violence, and honor the attacks with their own violence. The Buffalo and Bratislava attacks conformed to all three of these aspirations, this cultural script was also attempted in the failed plots in Italy and Sweden. There is a kind of “wiki effect” to these attacks, with each individual attacker contributing to the larger product of the far-right extremist movement. Each individual offers an ideological framing and/or a set of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) on how to carry out mass shootings to any potential future mass shooter and why it should be done. Given the copycat nature of extreme far-right attacks and case after case of individuals drawing inspiration from the likeminded terrorist actors who preceded them, this is of significant concern and a trend that will likely continue into 2023. There are forces in these ecosystems that play a role in radicalizing and mobilizing individuals, who have yet to carry out attacks, and are currently part of the IMVE propaganda feedback loop. An example of this is the recent arrest of an individual who went by the name BookAnon who was arrested in the UK earlier this year and was subsequently found guilty of five counts of encouraging terrorism relating to his creations. They also found him guilty of one count of possession of material for terrorist purposes, as he owned a 3D printer, which he had tried to use to make parts of a firearm. He now faces extradition to the United States. The 19 year old created propaganda, which likely inspired the Buffalo shooter, as screencaps from their video made it in onto the cover of the Buffalo shooter’s manifesto. Moreover, the Buffalo shooter also thanks BookAnon twice in his diary.

BookAnon and the Buffalo attacker were not part of the same group, and based on public information they did not communicate with each other. The Buffalo attacker did not know the Christchurch shooter, though he was inspired by him via the video of his terrorist act and his manifesto. The Bratislava shooter did not know the Buffalo shooter, though in his manifesto he said his attack is what inspired him to mobilize to violence. These individuals are not connected via personal interactions or by being part of the same group. They are connected by a shared propaganda network and the IMVE ecosystems they inhabit. However, these incidents do not occur ex nihilo, though these individuals may plan and carry out these attacks alone, they ecosystems they inhabit are one of the drivers. It is important to realize that this is a multifaceted challenge, at which we will never be 100% successful in preventing attacks.

4) Anti-Authority Violence

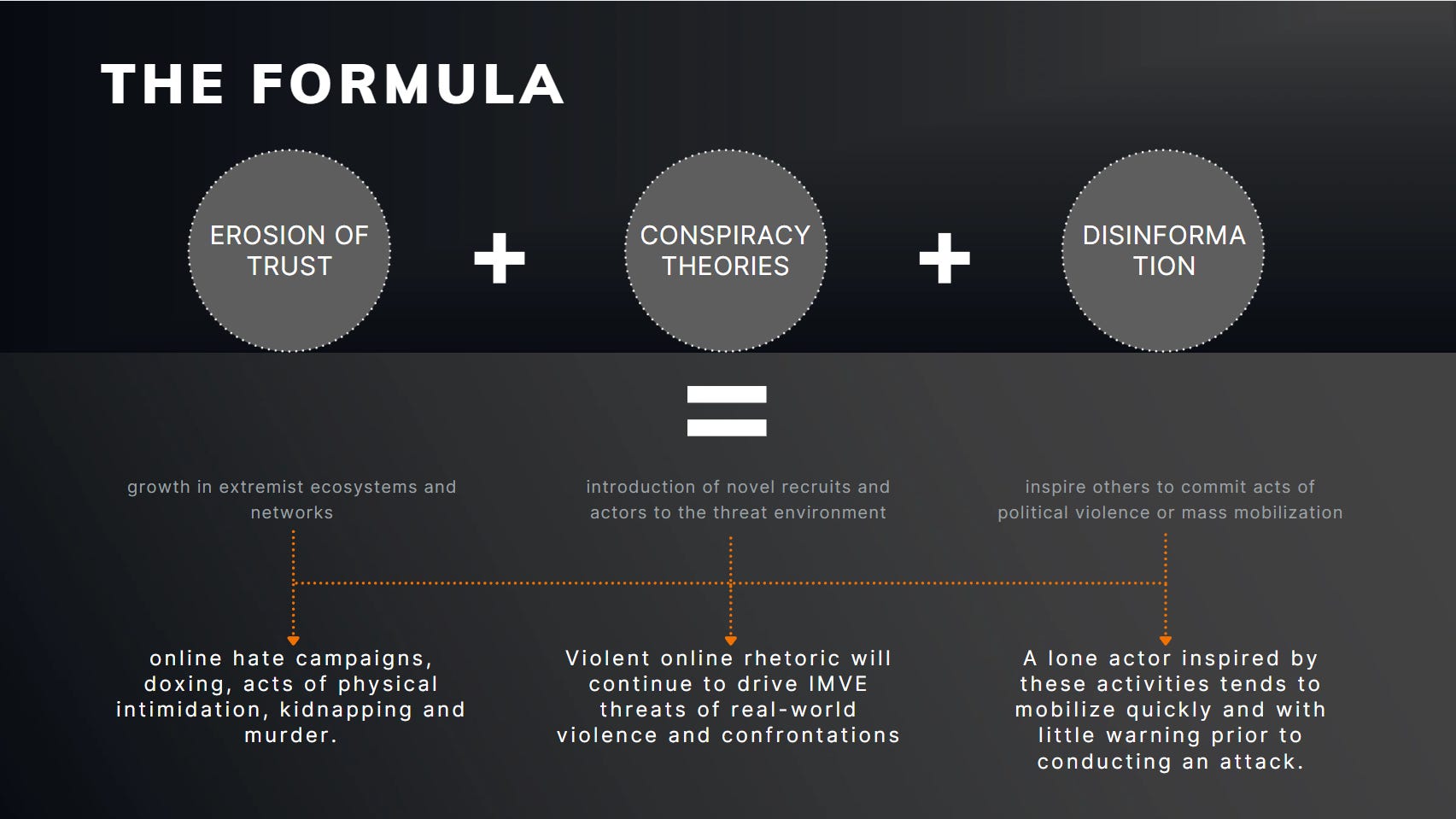

Another trend, which continues from the past year, is the rise in anti-authority extremism, which combines IMVE influencers and networks effectively leveraging the eroding trust in government, which is combined with a sustained growth of conspiracy theories and disinformation (both domestic and foreign). 2022 started with the Trucker protests in Ottawa, (which then became a transnational phenomena with similar protests in Australia, New Zealand, the US, Belgium, and France) and ended with the German government foiling a plot to overthrow the state by the Reichsbürger movement. Threats to elected officials and democratic institutions continued to be a key aspect of anti-authority violence in the US, Canada and abroad.

There is a formula I have found that most anti-authority extremists tend to follow:

The combination of these elements has lead to increased growth in violent extremist ecosystems and networks, the recruitment of followers (both traditional and novel) and the inspiration of others to commit acts of anti-authority violence or mass mobilization. Anti-authority IMVE activities have included online hate campaigns, doxxing, acts of physical intimidation kidnapping, murder.

There has been an increase in threats, attempted and successful attacks against: medical personnel, poll workers and election staff, law enforcement officers, judges and lawyers, academic institutions and teachers. As we have seen in in the past, a trend for 2023 in this space will be that violent online rhetoric will continue to drive IMVE threats of real-world violence and confrontations.

Dangerous conspiracy theories are an important factor to consider in 2023 threat assessments, as they are at the heart of many IMVE incidents in 2022. In example QAnon Queen of Canada had six of her acolytes arrested when they attempted to make arrests of Peterborough police officers in August 2022. Additionally, conspiracy theories were also central to the November 2022 attack on Nancy Pelosi’s husband by a conspiracy theorist. Moreover, 2022 also saw an additional 26 acts of violence and criminality from QAnon adherents in the US, Canada, Netherlands, Japan and Germany.

5) Gender & Identity Driven Violence

While several aspects of modernity are criticized by IMVE actors, one of the key points of convergence is their mutual disdain for progressive politics, characterized by feminism, pluralism, gender diversity and same‑sex rights. Gender-related violence does not only affect cis women; trans, non-binary, and gender-diverse individuals are at nearly four times a higher risk of violent victimization than cisgender and heterosexual populations. 2021 became the “deadliest year on record” for trans and non-binary people according to a report from the Human Rights Campaign, which continued in 2022. In the UK, police recorded a 19% increase in hate crimes against transgender people between 2019-2021. The report states “Transgender identity hate crimes rose by 56 per cent (from 2,799 to 4,355) over the same period, the largest percentage annual increase in these offences since the series began.” Transgender identities have been heavily discussed on social media over the last year, due to the introduction of new legislations, doxxing of trans people, and public statements by transphobic pop culture figures.

In 2023, violent rhetoric, from both online and offline sources of perceived or real authority, will likely continue to drive IMVE threats of real-world violence and confrontations. A pronounced intolerance to the LGBTQ+ community is common between many IMVE actors and movements. LGBTQ+ hate acts as the glue that can bring together the fractured and fractious IMVE landscape.

Gender and identity based violence has been at the forefront of several incidents of harassment, violence and murder in 2022. In example, Vice reported that the Proud Boys, in at least 11 different states, showed up to venues such as libraries and restaurants to intimidate drag shows, especially events touted as “family-friendly” such as drag brunches or the popular reading series “Drag Queen Story Hour.” Additionally, the Bratislava LGBTQ+ bar attack, and the mass shooting at the LGBTQ+ club in Colorado represents the most extreme manifestation of gender and identity driven violence.

6) Ecofacism

IMVE environmentalism will not be born from a vacuum. It would draw on the history of reactionary nature politics, seen in extreme-right ecologism. However, ecologism and environmentalism are seen through a fascist and metapolitical lens. Ecofascism is first and foremost an imaginary and cultural expression of mystical, anti-humanist Romanticism. Its vision is capable of inspiring political action, from propaganda to lone actor violence to parliamentary politics. (Hughes, et al, 2022)

The pandemic provided a glimpse into possible IMVE responses to future climate breakdown. Past responses to climate crises such as extreme weather events had been shot through with environmental racism and state violence, however, COVID-19 has moved the Overton Window. Like the Big Lie, the energy/climate crisis will continue to be used as a metapolitical tool by IMVE actors. This will once again bring together disparate ideological actors together in a common cause. Already in France, Germany and Italy there have been violence and protests stemming from rising fuel and natural gas prices. As winter comes and individuals need to make choices between heating and other necessities, narratives from IMVE actors and the solutions to the crisis will become more palatable, as was the case with the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Ecofascism” is also what the Christchurch mosque attacker called his ideology. He used it to justify murdering 51 Muslims. A few months later, the same justification was used in the killing of 23, largely Latino or Latina, people in El Paso. Ecofascism was used to justify the killing of 10 African Americans in Buffalo, in March 2022, and was also part of the Bratislava shooter manifesto. In their manifestos, they equate immigration or the presence of other races with environmental warfare. Why do they focus on immigration and birth rates when climate change is such a huge issue? They believe that they are the same issue. Climate change and the Great Replacement are unified through their shared sense of catastrophic non-localizable crisis and both require an immediate and violent response.

A key trend I have noticed is a large increase of Ecofascist Telegram channels and chats appearing in the past year, where those that I monitor have increased from 14 in 2021 to 62 in 2022. What is of note is how these are linked to the wider accelerationist ecosystem on the platform.

7) Accelerationism

Accelerationism is most broadly understood to be a recognition that modernity, liberalism, and capitalism’s inherent flaws are the source of their own inevitable and accelerating demise. (ARC, 2022) The manifestation of accelerationism that I have observed the most over the past year is that of militant accelerationism which is “a set of tactics and strategies designed to put pressure on and exacerbate latent social divisions, often through violence, thus hastening societal collapse.” (ARC, 2022)

The challenge with accelerationism, is that it has also become an aesthetic for many in these ecosystems, as much as it is a set of tactics, techniques and procedures for carrying out acts of terrorism, making it difficult to navigate the threats vs shitposters as the lines become blurry.

A key network in this space, in 2022, was the Terrorgram Collective. Formed of a series of channels and actors, the collective has published several manifestos over the past 18 months that contain ideological and instructional material, as well as potential targets of attacks. Two of these manifestos were published in 2022, along with a documentary. One of the instructional documents was aimed at a younger audience, instructing them in acts of acceleration that do not involve bodily harm as a way of easing them into more violent actions. The Bratislava attacker thanks the Terrorgram Collective in his manifesto for their publications and makes several nods at these documents within his writing. Due to the mention of the Terrorgram Collective in the manifesto, the network of channels and chats associated with the collective were heavily invested in consuming and amplifying the document among themselves on Telegram and rapidly turning it into an audiobook. This was the first known instance of the Terrogram Collective very likely influencing an individual to carry out an attack, along with several other factors.

Accelerationism will continue to pose a threat in 2023 not only from individuals carrying out mass attacks, but also with the potential of individuals carrying out attacks against critical infrastructure.

8) Critical Infrastructure

The targeting of critical infrastructure is often found in accelerationist and ecofascist propaganda. Targets of particular note from publications, videos, and multimedia content released in these ecosystems are: cell towers, power substations, transformers, and calls to sabotage air conditioning units during heat waves or derailing trains by loosening bolts on train tracks. Some propaganda material also contains instructional material from low tech/ low budget options, to more sophisticated methods of attack.

Attacks on critical infrastructure are not only threatened by accelerationists; during the COVID-19 pandemic, conspiracy theories about 5G technology being linked to the spread of the virus lead to a series of attacks against cell towers. Attacks against critical infrastructure were also carried out by neo-luddites, anarchists, anti-capitalists and environmentalists. Moreover, on July 16, 2020, US officials believe that a drone, with a thick copper wire attached underneath it via nylon cords was likely at the center of an attempted attack on a power substation in Pennsylvania .

Most recently, there were six attacks against power facilities in the Pacific North West, as well as two more in North Carolina. The investigations are still ongoing; however, the impact of attacks against critical infrastructure can be dramatic on local populations, in particular during the cold of winter or during heat waves. With an energy crisis in the EU, and the demonstrated impact of recent attacks in the US, it is a threat vector to keep an eye on for 2023.

9) 3D Printed Guns

Over the past three years, the threat of extremists and terrorists making 3D-printed guns has changed from a hypothetical to a realized scenario. Since 2019, there have been several examples of extremists, terrorists, or paramilitaries making, or attempting to make, 3D-printed guns in Canada, Europe, South-East Asia (SEA) and Australia. There has been some fantastic work done by Rajan Basra and Yannick Veilleux-Lepage on these topics.

The ideological use of 3D printed guns is not ubiquitous in some milieus, where some movements and groups equate the use of 3D printing for making firearms as a failure on the part of an individual when it comes to stock piling weapons, a very popular sentiment within US based ecosystems. However, this is not as common outside of the US, especially in countries where obtaining weapons or automatic weapons is more difficult.

Of note, 3D printing is not only about printing guns. 3D printing also offers IMVE actors the opportunity to create parts to modify existing weapons, their tactical gear, as well as help create parts for explosives or modify drones.

Rajan makes a key point in his piece however:

Tactical innovation in terrorist attack planning can rely on a ‘breakthrough moment’. That can be via the release of propaganda or a high-profile attack, which signals to other extremists that this new method works. 3D-printed guns have not yet had this breakthrough moment. However, the recurrence of plots since Halle shows that such a breakthrough may not be necessary. Despite this flurry of cases, it is essential to maintain perspective. Improvised, homemade firearms—and documents instructing people how to make them—have long predated the rise of 3D printing. The vast majority of the hobbyists and enthusiasts of 3D-printed guns likely have no intention to use them for terrorism. Even then, the greatest threat does not appear within this community but rather from existing extremists coming across—or deliberately searching for—their designs.

What I have seen in 2022, is an increase in plots involving 3D printed weapons or components, as well as an increase in the sharing of 3D printing instructions, cad files and resources in IMVE ecosystems. 3D printing is a trend that we should keep a close eye on for 2023, especially as there continues to be innovation in this space from hobbyists, new printing methods and materials are made available to the public and costs become less prohibitive. Further, with the viability of 3D weapons being tested in theater in South East Asia, it is a matter of time before 3D printing has its breakthrough moment in relation to IMVE.

10) Platform Shopping

Platform shopping, which is when maligned actors experiment with various platforms, usually when certain services become too hostile towards them is something that has been happening with the Terrorgram Collective and their digital assets in the second half of 2022. Though Telegram is mostly permissive of IMVE content on its services, there are specific branded digital assets on Telegram that are regularly taken down in a game of whack-a-mole. Google store and Apple store have also played a role in blocking specific digital assets on Telegram that are violating their ToS. When these digital assets are taken down, they are immediately set back up by the channel/chat admins; however, there are times when data and propaganda is lost by IMVE actors when takedowns do occur. Furthermore, IMVE actors work under the presumption that most chats and channels have been infiltrated by researchers, journalists, anti-fascists and law enforcement. This sense of paranoia is a key cultural phenomena in these spaces; however it does make actors in these space more aware of their own operational security.

The Terrorgram Collective’s propaganda assets have increasingly fallen victim to regular purging which has forced the actors administering them to shop around for alternatives. Questions around how private Telegram really is also has forced actors to shop around. Some of the main platforms that have been tested this year are Wire, Matrix and TamTam.

Wire is and end-to-end-encrypted (E2EE) messaging and collaboration application. Some threat actors have moved some of their activities to Wire; however, usually Wire is where you will find individuals who are already part of these ecosystems, or where the vetting process can occur. You will often find a Wire contact on terrorist owned and operated websites to contact a group or recruiter, as an alternative to Protonmail. Wire contact info has also been embedded in GIFs and overlayed in Videos as a way of avoiding detection. Wire also offers a fair amount of protection to the users who are using it, and do not offer an API or an extract function to save chat data as Telegram does.

TamTam is a shoddy Telegram clone; notorious for housing child sexual exploitation and/or abuse material and having no real content moderation efforts. Moreover, as Amarnath Amarasingam has highlighted, TamTam was also a refuge for ISIS fighters, when Telegram banned all their digital assets from its platform. This year, the Terrorgram Collective, and associated network of actors, started moving 18 of their propaganda channels and archives to TamTam. For the most part these were back up assets to the main ones on Telegram. In November, however, admins in the ecosystem started pushing for users to move to TamTam, as a safe haven from moderation, even branding the TamTam network as Terrortam. On December 5th TamTam, in a surprising step, took down the assets linked to the Terrorgram Collective. The chilling effect on the Terrogram Collective was felt immediately as frustrated admins deemed TamTam to be compromised by actors seeking to silence them, rather than trying to play whack-a-mole like they usually do with Telegram.

Since December 5th, and the journalistic reporting around the take downs, the Terrorgram Collective and other accelerationist inclined digital assets have been exploring decentralized P2P apps, personal Internet Relay Chats (IRC), or Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP) as alternatives. A popular option being discussed is Matrix, which is an E2EE messaging protocol. IMVE actors in these ecosystems are experimenting with Matrix rooms, though there are some challenges. The most important of which is that IMVE actors do not want to use a public server, this requires that a member of the community runs a homeserver, which can then connect to the federation. However, as an end user, within a culture of paranoia, you need to trust the person running the homeserver. This is not the best avenue for propaganda; however, this might be an avenue for secure messaging. Of note for researchers, analysts and reporters, there are some important OPSEC implications in terms of joining IMVE servers run by known threat actors. (something I will explore more in 2023)

Looking forward

Though it has been a tumultuous year in terms of IMVE, with a number of significant events and trends emerging over the course of 2022, this is a summary of the top 10 trends I have seen in my research and analysis in the past year. There is plenty of dimensions that I have not mentioned here, simply because I have not had time to examine them or they are not part of my repertoire in terms of interest and expertise. Please do not take this as an exhaustive list, but as a starting point for potential avenues of research and analysis in 2023.

Next year, I will be working on a series of posts with tips about operational security for new academics, senior researchers and practitioners working in this space, as well as doing dives via data I have collected on specific actors and ecosystems in the IMVE ecosystem.

From the Depths is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.